The right combination of image-processing performance and low power consumption is best achieved by specialized on-device vision and neural-network processors

Some technologies seem to spring fully formed out of nowhere, while others need years, or even decades, to become widespread and popular.

Virtual reality (VR) and its close cousin, augmented reality (AR), definitely fall into this latter class. The earliest prototypes were built in the 1960s, and while there have been many false starts, we’ve yet to see VR and AR become commonplace in the way that many people predicted. In the last few months, there have been some high-profile failures: AR startup Blippar raised more than $130 million but went into administration in December 2018, while 2019 has already seen two well-known VR/AR startups shut down: Meta and ODG.

There have been indications that AR and VR were about to finally break out of their existing niches. When Google launched its smart glasses in 2012, there were predictions that it would change the world, but it never gained mainstream adoption. Similarly, when Facebook bought Oculus for $2 billion in 2014, it looked like a tipping point had been reached, but sales of Oculus’s VR headsets have disappointed.

With such major backers, why has VR/AR failed to go big?

It’s arguable that the limitations in available software have meant that there’s no “killer app” that makes everyone want a VR/AR headset. Some games have gained strong followings, but there’s been nothing that has made your average gadget aficionado feel that they really must pay hundreds of dollars for a VR/AR set.

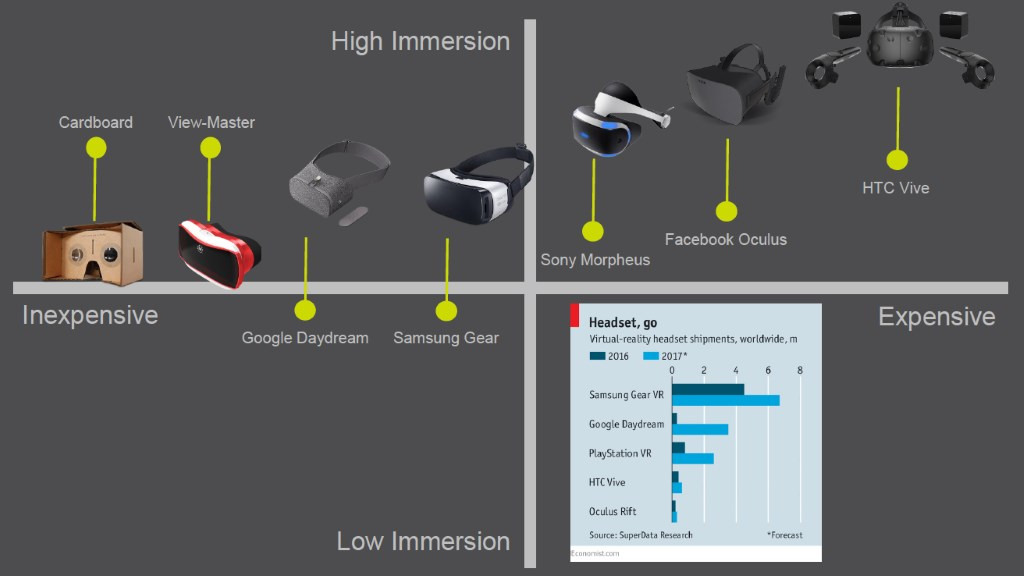

On the other hand, it’s just as true that the available hardware has not quite been there yet. There is a huge range of products already available, as well as software solutions like Apple’s ARKit 2. But there are many challenges still to overcome before adoption goes truly mainstream, including computing power, latency, and power consumption, as well as cost. If devices cannot offer immersive processing in a compact wire-free package with decent battery life, they will fail to find a place in consumers’ hearts.

The state of play for VR/AR devices

In January 2019, Juniper Research predicted that more than 100 million mobile VR devices, including smartphone and standalone headsets, will be used for gaming by 2023. They also expect revenues from VR games to grow from $1.2 billion this year to over $8 billion in 2023.

So what is different now? And what are the key challenges facing developers of AR/VR hardware today that must be overcome to make these predictions come true?

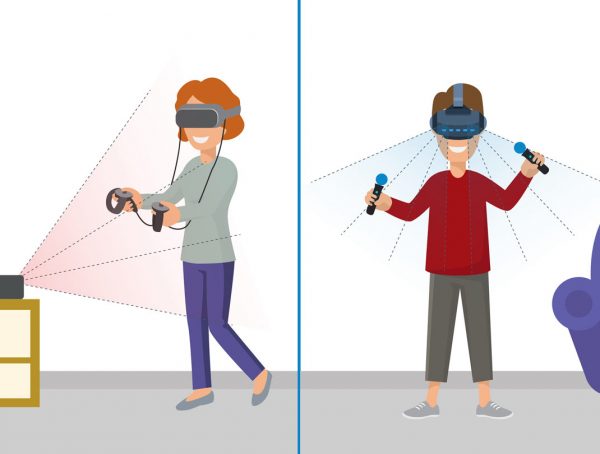

There is a huge range of VR solutions on the market now, with a variety of head-mounted displays (HMDs). Figure 1 shows some examples: Those at the left use the display and processor of a smartphone that fits into the headset, while those on the right need to connect to a PC or gaming console, which means that the user is restricted by wires.

Figure 1: Popular HMDs (Source: CEVA)

Devices announced recently at MWC 2019 — such as the Microsoft HoloLens 2, the Varjo VR-1, the Vuzix M400, and the Magic Leap One — are targeted at either developers or enterprise users and are priced out of the consumer’s reach. In my opinion, only the mobile devices are able to deliver the right user experience that is necessary for mass adoption.

That said, the upcoming Facebook Oculus Quest and its competition, the HTC Vive Focus Plus, both launching later this year, are untethered, all-in-one headsets that don’t require a smartphone to handle processing. They promise big things, if early reviews are to be believed.

Meeting the image-processing challenge

Whatever the system, one of the most important requirements for VR/AR is to provide an ultra-high-resolution display so that the user can feel involved in an immersive experience. This requires a lot of image processing and — these days — neural-network (or artificial-intelligence [AI]) power, both of which are tough challenges for existing mobile devices.

For all of the HMDs that require tethering to other hardware, the user is always going to feel restricted by the cables. In addition, many of these systems use “outside-in” tracking, wherein the user’s movements are detected by fixed sensors placed around the room. This further adds to the cost and complexity of the system in which the consumer must invest.

The alternative, used by mobile HMDs, is “inside-out” tracking, wherein the motion sensors are located on or in the portable device itself. This means that the user can move around freely, not just in a room that’s been specially set up. However, this needs some clever processing by the device, which adds to the computational requirements as well as the performance capabilities needed.

For AR, the tracking challenge steps up a gear. In addition to determining the user’s position and movements, the system must map the space in which they are located. This is termed “simultaneous location and mapping” (SLAM), and it is essential to enable virtual objects to be positioned accurately in relation to the real environment, as a lack of precision can detract from the user experience.

Assuming that appropriate sensors are chosen, the key to good mobile VR user experience is for latency to be minimized, as a lag more than a few milliseconds long will be noticeable, particularly for VR/AR gaming.

Importantly, the image-processing hardware must not consume too much power; otherwise, battery life will drop below acceptable levels or the device will require a cumbersome and heavy battery pack.

The right combination of image-processing performance and low power consumption is best achieved by specialized on-device vision and neural-network processors. These processors can also handle other tasks required for VR/AR, including tracking, foveated rendering, and AI.

What happens now?

While VR/AR has often appeared about to take off, only to disappoint, today, we have better technology than ever before, with high-performance image-processing hardware that can deliver the dazzling capabilities required without draining a device’s battery too quickly.

(Source: Shutterstock)

The major headset vendors are iterating toward more mature designs, and they are using their years of experience to deliver hardware that meets consumers’ expectations. Opinions are more mixed on where we stand on software: Some major publishers have slashed their investments, but AR and VR titles are being developed all the time, and the potential is there for a breakthrough hit to drive hardware adoption sooner or later.

Of course, the real mark of mainstream adoption would be for VR/AR to break out of its gaming and early-adopter niches and to become a standard part of our living rooms. That may be too much to hope for just yet, but the technology that could make it a reality is already here. Only time will tell whether its moment has now come.

Published on EEWeb.

You might also like

More from Imaging & vision

Challenges in Designing Automotive Radar Systems

Radar is cropping up everywhere in new car designs: sensing around the car to detect hazards and feed into decision …

Transformer Models and NPU IP Co-Optimized for the Edge

Transformers are taking the AI world by storm, as evidenced by super-intelligent chatbots and search queries, as well as image …